It Has Been 45 years Since That Tragic Night

It was a malevolent irony that after Bill Smith survived a year-long combat tour in Vietnam and was awarded the Silver Star, the Marine Corps third-highest medal for gallantry, he returned home to Denver and became a police officer only to lose his life when he walked into a North Denver bar for what he thought was a minor disturbance call that turned out to be an armed robbery in-progress.

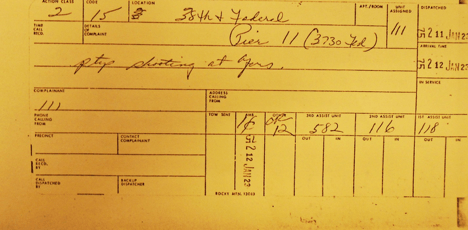

The series of events that led up to his death in the early morning hours of Thursday, January 23, 1975, began at 1 a.m. when two men went looking for trouble at the Pier 11, a small, somewhat forlorn neighborhood bar located at 3730 Federal Blvd. After consuming a few beers, the larger of the two tried to pick a fight with another customer, whom he had goaded into arm wrestling him. The bartender, Marilyn Sue Apodaca, 32, saw what was happening and asked the two men to leave, saying she didn’t want any trouble.

The one who tried to start the fight stood well over six feet tall and had a stocky build. He wore a brown turtleneck under a brown, knee-length corduroy coat. He had long, dark straight hair parted in the middle. His name was David Bridges, 26, and he was the subject of a four-page, multiple-state rap sheet which listed his long history of arrests for such crimes as child molestation, rape, narcotics violations, robbery and check fraud. He worked at a gas station at 44th and Federal.

His companion was James Lang, 24, a much smaller man, who wore a t-shirt under a gray jacket. He had blond curly hair and a boyish expression that invited comparison to Bridges’ angry scowl.

They told Apodaca they would leave, but only if she gave them each a shot of whisky. After drinking the shots they went outside. At 1:55 a.m., Apodaca stepped out the side door that led to the parking lot on the south side of the building, looked to her left and saw them leaning against a car parked at the far end by the alley.

She went back inside and locked the side door, then the front door that faced Federal. She warned the few remaining patrons that the two troublemakers she had asked to leave were still in the parking lot and for them to be careful when they went out to get in their cars. Two regular customers, Norman McVay, 40, and Ronald Schafer, 33, offered to stay with Apodaca until she closed up for the night. She was grateful for their offer. A third, Bob Moriarity, 41, said he too would stay, but she told him that wouldn’t be necessary.

When she unlocked the side door for Moriarity and an older couple to leave, Bridges and Lang took the opportunity to come back inside. Exasperated, Apodaca told them she was going to call the police and walked over to the telephone. Before she could dial, however, Bridges grabbed the receiver from her and slammed it down hard on her hand, threatened her, then stormed back outside with Lang.

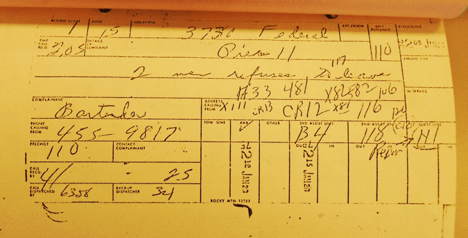

She quickly relocked the side door behind them and called police. She told the call taker that she was having trouble with two men who were drunk and refusing to leave. The time was 2:05 a.m. After she hung up, Moriarity knocked on the side door, said he had forgotten his jacket and asked to be let back in to get it.

Apodaca gave Schafer the keys and asked him to let Moriarity in. When he did, Bridges and Lang pushed their way in, taking Moriarity with them. This time they had guns: Bridges a .357-caliber Hawes revolver, and Lang a .22-caliber Marlin semi-automatic rifle with the stock removed. The guns had been stashed in Lang’s car, next to which they had been seen standing.

Bridges announced the robbery and ordered Apodaca and the three customers to lie on the floor.

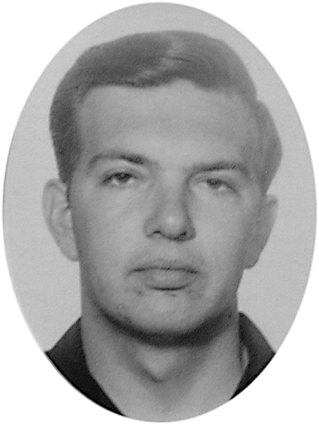

Photo Credit: Denver Police Department

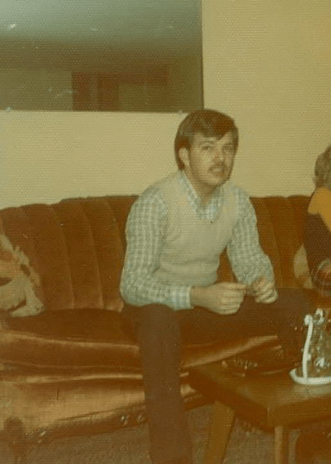

In this undated photo, Bill Smith was shown relaxing with friends.

Courtesy of Cathy Thomas

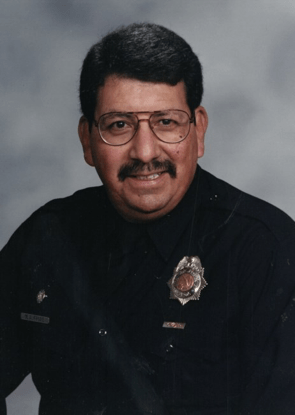

This photo of the late Officer Mark Frias was taken about the time of his retirement in 2007.

Courtesy of Nancy Frias

The disturbance call of “two men refuses to leave” at the Pier 11 was aired on Channel 1 as soon as it was received in the radio room at Police Headquarters. Car 110, Officers Mark Frias and Bill Smith, was assigned the call since the bar was located in their precinct. Like Smith, Frias was a Vietnam veteran. He had served in the US Army. Both had worked in District One since graduating from the police academy. They enjoyed working in Sector 1, which encompassed much of North Denver. They had worked around each other for quite a while and had developed a friendship, but had only recently become steady car partners.

Car 111, Officers Aaron Burroughs and L.C. White, was assigned to cover them. The end of the shift for the four officers was less than an hour away. It had been a long, cold night, and the officers were looking forward to getting home.

Sergeants Lloyd Baca and Robert Dunkley who were riding together in cruiser 12 also covered the call.

In the six minutes, between the time Bridges and Lang announced the stickup and when the officers arrived on the scene, the two gunmen terrorized Apodaca and the others.

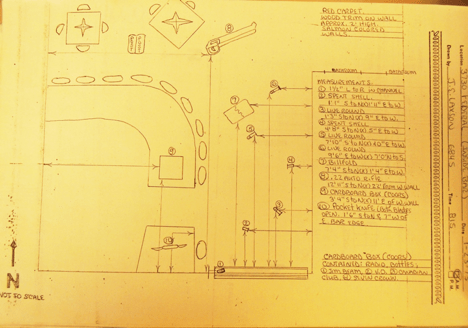

Wanting to scare their already frightened victims, Lang blasted away at the shelves of liquor bottles hung on the salmon-colored wall behind the bar. Bridges went behind the bar where Apodaca was lying, stepped on her, then poured an entire pot of hot coffee on her back. She said later she wanted to cry out, but did not for fear he would do worse. He then emptied the cash register, while Lang took the wallets from the three men lying on the red-carpeted floor. One of the gunmen put four bottles of liquor and a small AM-FM radio in a cardboard box on the bar to take with them.

When Apodaca heard the side door open, she knew it was the police and they would soon bring an end to her ordeal. Then she heard two shots, a loud groan, then more gunfire.

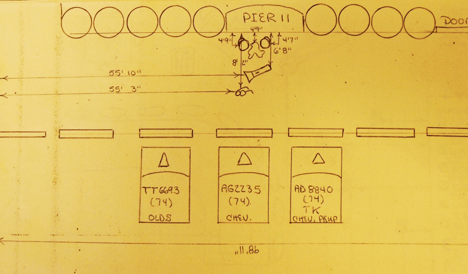

When Frias and Smith drove into the parking lot, they saw three unoccupied cars parked by the side door and a fourth car, also unoccupied, parked next to the alley. On the windshields was a light dusting of snow, suggesting they had been parked there for a while. Both officers had been to the bar on calls many times before. Looking around, all appeared as it should; there was nothing to indicate trouble, nor was there anyone waiting around to warn them of the much greater, but unknown danger that awaited them inside the bar.

Frias, a three-year veteran of the police department, parked the car. Smith, a five-year veteran, got out the passenger side and began walking up to the side door. It is not entirely clear why Smith was first to the door. Depending on how Frias had parked the car, Smith’s side may have been closer to the building; or, perhaps, Smith was just quicker to get out of the car since Frias had to take the car out of gear, turn off the headlights and engine, get his flashlight and put on his hat before getting out, then secure the keys to his gunbelt or put them in his pocket. Whatever the reason was for one of them get to the door ahead of the other would make all difference this night of who would survive and who would not.

Smith clipped their portable radio to his gun belt. In his left hand he held his flashlight. He carried nothing in his right hand in case he needed to draw his service revolver.

There were no windows on the south side of the building, except for one small, diamond-shaped window in the steel side door. Officers usually looked through it before going into the bar on calls. It is unknown if Smith did so this time before pulling open the door to step inside.

Bridges was standing at the end of the bar nearest to the door, less than six feet away from Smith. He fired twice; one round struck Smith just below the center of his chest, causing him to stagger back and fall just outside the door. Frias, who was about three paces behind him, heard the shots and reacted immediately by firing twice at Bridges as the gunman ran out the door into the parking lot towards the alley.

Bridges may have hesitated at Lang’s car, uncertain if he should get in and drive away or continue running. It was struck by two police bullets in the left, front quarter-panel and driver’s-side door.

Burroughs and White arrived on scene just as Smith was walking up to the door. Burroughs fired five times at Bridges running in the parking lot. White transmitted that shots had been fired and an officer was down.

Bridges turned at the corner of the building and started running northbound in the alley with Frias in pursuit. Frias fired four more times. When he stopped to reload he lost sight of Bridges.

Burroughs started running north on Federal and fired one more shot at Bridges crossing 38th Avenue. Baca and Dunkley saw Burroughs running and drove up to him. “They shot Smitty!” he yelled over to them. Dunkley called for an ambulance, then jumped out and joined Burroughs pursuing the suspect on foot, while Baca drove to the Pier 11 to take charge of the scene.

It was shift-change time and there were perhaps 20 officers at the District One station, then located at 2195 Decatur St. Upon hearing White’s emergency transmission, the station emptied out as everyone ran to their cars and race to the scene. The Channel 1 dispatcher patched together the four primary radio channels, sounded the alert tone — called a turkey call because of the sound it made — and broadcast, citywide, that officers were calling for help at the Pier 11.

Hearing the heartening sound of incoming sirens signaling that help and lots of it was on its way, Frias ran back to his partner.

Meanwhile, Lang had remained inside the bar. He dropped the rifle in an effort to pass himself off to police as just another hapless customer. Off-duty, uniformed District 1 Officer Dennis Cribari, who had heard the commotion and had come running over from a restaurant across the street where he was eating, burst into the bar. Apodaca quickly pointed out Lang as the second gunman and he was arrested.

Joining Baca and Frias at Smith’s side was Officer C.M. Torres on car 120. His partner, Eugene Robinson, had dropped him off before joining in the search for the suspect. Each of them – and there were others too — knelt down and tried to comfort Smith. They waited for what must have seemed like an awful long time for the ambulance to arrive. Almost certainly, each of them said a silent prayer.

Denver General Ambulance 1 got there as soon as it could. Just as police officers respond as fast as they can when one of their own is down, so too did DGH paramedics when an officer was wounded. Paramedics Brown and Warriner rushed Smith to Denver General Hospital. Torres and Robinson went with them.

Scores of officers from District 1 and other districts scoured the area looking for Bridges. One of them was District 1 Officer Robert Wallis. He had already experienced, first-hand, the death of a fellow police officer. Four years earlier, he had held District 2 Officer Merle Nading in his arms after Nading had been mortally wounded trying to break up a disturbance at a restaurant in East Denver. Sadly, Wallis, as an auto theft detective in 1988, was himself killed in the line of duty when he was intentionally struck by a robbery suspect fleeing police in District 1.

Sergeant Dunkley established a perimeter of containment north of the shooting scene by posting officers at intersections and alley entrances. Others drove around slowly inside the perimeter, shining their lights at the many dark recesses and shadows, hoping to flush the suspect. Some officers got out on foot and walked in pairs inside the perimeter, looking for fresh footprints or blood in the snow, fence gates ajar and doors and windows that may have been forced open.

Two such officers were Bill Bierbach and Larry Carmer on car 106. They had parked in the 2800 block of West Denver Place and started searching to the south and west between the houses. They stopped to talk to Steve Scott, an employee at the for C & C Towing office. He told them he had seen a man running at the Pay and Pack plumbing supply store then turn into the alley next to it.

Bierbach soon saw fresh footprints in the snow along the fence on the east side of the store. When he climbed onto a fence to get a better look at the garage roof at 2952 W. Denver Pl., he saw the suspect lying face down between two sheds. The time was 2:30 a.m.

Holding him at gunpoint, he yelled for Carmer to approach from the opposite side. Thus contained, Bridges was ordered to stand up and surrender. He refused. Other officers, including Wallis, ran over and together they pulled Bridges out, handcuffed him and called for an ambulance. He had been shot three times in the abdomen and thigh.

A third ambulance took Apodaca to the hospital to treat the burns on her back.

Officers Paul Mueller and Mark Roggeman on Post 11, recovered Bridge’s revolver from a doorway in the rear of a laundry at 2936 W. 38th Ave. The cylinder contained only two cartridges, both of which had been fired.

Bill Smith was pronounced dead at 3:17 a.m., a little over an hour after he had been shot. The bullet had exited out his back. It was discovered beneath him on the gurney in the emergency room. He died from a loss of blood, according to Dr. Lawrence Norton.

After leaving the scene, the night shift commander in District 1, Lieutenant Morahan, went to Smith’s parents’ house in Englewood. It was his grim duty to wake them up in the middle of the night and say to them the words no police commander ever wants to have to say, and that no policeman’s family ever wants to hear. It may have been the hardest thing he had to do in his long career. He then drove the family to Denver General Hospital.

Later that same morning, hundreds of Denver Police officers, outraged that Smith had been killed by a hollow-point bullet while Frias and Burroughs had to rely on more traditional round-nose bullets with less penetration and knock-down power to stop Bridges, gathered en masse to voice their grievances. As many as could fit in his office met with Chief of Police Art Dill. Widely heralded as a “cop’s cop,” Dill agreed that his officers should be allowed to use hollow-point bullets and have access to shotguns in patrol cars. (For the time being, officers could start using hollow-point rounds, but they would have to be bought at their own expense. It would not be until April of that year that shotguns were purchased for patrol cars.)

The chief’s decision set off a political firestorm at the local, state and even federal levels. Denver City Council members, Colorado General Assembly legislators as well as Governor Richard Lamm, along with at least one Congressional Representative from Colorado weighed in, saying that giving police hollow-point bullets and shotguns was overreach and a knee-jerk reaction to a tragedy that would not have been prevented even if officers had had that kind of ammunition and access to shotguns at the time of the shooting.

Dr. Norton, who had tried desperately to save Smith’s life, agreed, saying that he would have died no matter if the round that struck him was a hollow point or round-nose ammunition, because the bullet had cut several veins needed to return blood to the heart.

Still, Denver officers were not satisfied.

The Denver Police Protection Association union announced a protest march that Saturday (in the afternoon, following Smith’s funeral service in the morning) to draw attention to the “irresponsible and overbearing political control of the Denver Police Department and the desperate need for more progressive and better police equipment.” It started in the 1100 block of Broadway, in front of the mayoral campaign office of Denver District Attorney Dale Tooley. Hundreds of uniformed and plain clothes officers then went to the City and County Building, and later the State Capitol to rally on the west steps.

Joe Garcia had been Smith’s long-time partner on car 110 until a few weeks before the shooting, when he was transferred to the Vice and Narcotics Bureau. The two had developed a solid friendship both on- and off-duty. Smith was considered by Garcia’s two children, then 11 and 12 years old, as something of a favorite uncle. He would sometimes come over to the house and let the kids play policeman wearing his uniform cap.

Someone called Garcia that morning and told him what had happened. What troubled him the most was learning that Smith had not had on his bullet-resistant vest when he was shot. He would have almost certainly survived if he had. When they worked together he always wore it, Garcia remembered; he wouldn’t go to work without it. Why on this night of all nights would he choose to leave it in his locker at the station or at home? Many other officers who knew Smith wondered the same thing.

Bullet-resistant vests or soft body armor, the kind worn underneath an officer’s shirt, are ubiquitous in law enforcement today. But in 1975 they were bulkier and less comfortable than today’s versions, so fewer officers were inclined to wear them. Smith was one of the few who wore one on a regular basis.

Garcia thought of Smith as a brother. He was quiet and reserved, and was not an easy man to get to know. He didn’t like to talk about himself, especially about his experiences in Vietnam. He was patient and a good listener to the frequently difficult people they encountered at work. He was unfailingly polite and never cursed, Garcia recalled.

Garcia knew he could count on Smith when the chips were down. He “always had my back,” and “was not afraid of anything.”

In the black-and-white world of the policeman, where those who broke the law and exploited the vulnerable were the bad guys, and those who enforced the law and tried to help people were the good guys, Bill Smith was among the very best of the good guys.

Another officer remembered Smith as one “squared-away Marine, all spit and polish.” He always looked good and carried himself well. Clearly, he liked his job and was good at it.

Smith liked ethnic food. At work he and Garcia would often eat at some of North Denver’s well-known Italian restaurants, such as Luchuga’s on Tejon Street, Patsy’s on Navajo Street or Carl’s Pizza on 38th Avenue. Smith liked to listen to rock and roll on the police car’s AM radio.

Wanita Frias is Mark Frias’s sister-in-law. She still remembers when she met Bill Smith. She just happened to be at Frias’s parents’ house in North Denver when Frias brought Smith over to meet them – something car partners seldom do with one another. Frias must have so pleased to have Smith as his partner and friend that he wanted to show him off to his family.

Wanita, only 22 at the time and newly married to Mark’s younger brother, David, remembers him well. He was remarkably warm and friendly and very polite. She, like the rest of the Frias family, was happy that Mark had such a good man as a friend who was also such a good car partner.

Then two weeks later he was killed.

On the morning he died, Wanita went to work as she normally did. She got a telephone call telling her to come home right away. That nice, young man she had just met had been killed a few hours earlier by a coward with a gun. The whole family was deeply saddened, but also relieved that it could have just as easily been Mark who had gone through that door first.

There was no one in department who took Smith’s death harder than Mark Frias. To his credit, he remained in District 1 for several more years, even after he was given the choice to go to other districts to work. He stayed on car 110 for some of it. He bore his suffering in silence, and did not like to talk about what happened that night.

Eventually, he left District 1 to work at Headquarters in the Vice and Narcotics Bureau, Gang Bureau, and later at the Denver District Attorney’s Office. He retired in 2007 after serving 34 years on the Denver Police Department.

He died on April 24, 2019. He was 69 years old.

His widow Nancy Frias, who married Mark some 20 years after the shooting, said he never wanted to talk to anyone about what happened, but once confided in her about it. He wondered why it had to be Smith who died that night and not him. Every year, on January 23rd, he would relive that night and have a terrible time trying to sleep.

He deeply mourned Bill Smith’s death, she said. He told her Smith was a good man and a good partner.

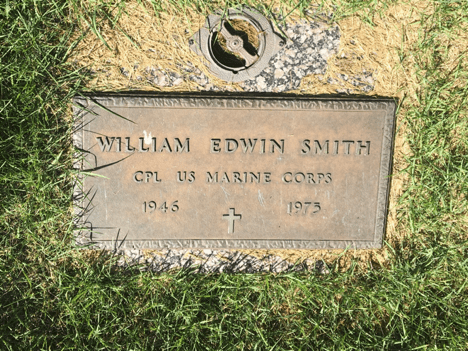

William Edwin Smith was 29 years old. He was born in Detroit, Michigan, on New Year’s Eve in 1946. He was survived by his parents, William and Ethel Smith, and two sisters, Joan Troppman and Jeannie Smith. He lived at 1442 Garfield St. The Smith family lived at 4188 S. Washington St. He graduated from Englewood High School in 1965.

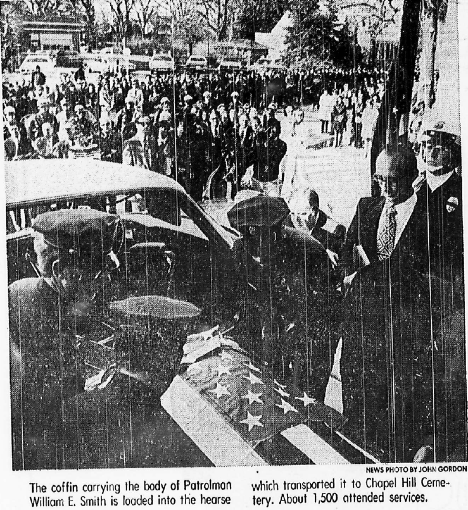

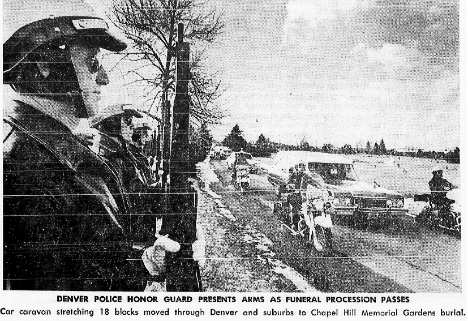

Funeral services were held at Olinger Mortuary at East Colfax Avenue and Magnolia Street at noon on Saturday, January 25. Some 1400 people attended, including some 700 members of the law enforcement community. The service was conducted by a Denver Police chaplain and a minister from the Smith’s family church, Fellowship Baptist Temple in Littleton.

An 18-block-long procession drove from the mortuary to Chapel Hills Memorial Gardens in Littleton, where he was laid to rest with full military and police honors. Frias and Garcia were among the District 1 officers who were pall bearers.

Smith’s father and mother, who died in 1998 and 1983, respectively, are buried next to him.

David Bridges did not live long enough to stand trial. He died from his wounds in Denver General on February 24, 1975. Lang did stand trial. After his public defender asked for and was given a change of venue citing a prejudicial pool of potential jurors in Denver, the trial was moved to Salida, Colorado. In June, 1976, he was convicted and sentenced to serve 5 to 8 years for aggravated robbery and life in prison for his role in the murder of Officer Smith. He was released from prison in 1990.

Crime scene evidence was taken out of the Denver Police property bureau to be used in the trial in Salida. Afterwards, most of it was returned and eventually destroyed. Two keys pieces of it – the murder weapon and the rifle – however, somehow got overlooked and remained in the Chaffee County Sheriff’s Department property room, until 2013, when a routine inventory discovered the guns. Undersheriff John Spezze, a retired Denver Police sergeant, contacted DPD. After determining there was no legal obligation to keep them in police custody any longer, they were donated to the Denver Police Museum.

It has been 45 years since that tragic night. Gone are most of the people who were there and the building itself, which was razed many years ago. There is no one left on the department who was even on The Job in 1975. Still, many others who knew Bill Smith continue to silently mourn his death. A portrait of Smith hangs in the District 1 station alongside those of two other District 1 officers who were killed in the line of duty since. On Federal Boulevard, just north of where the Pier 11 had been, a memorial sign was dedicated to honor his sacrifice.

Lest we forget.

© Bill Finch 2016