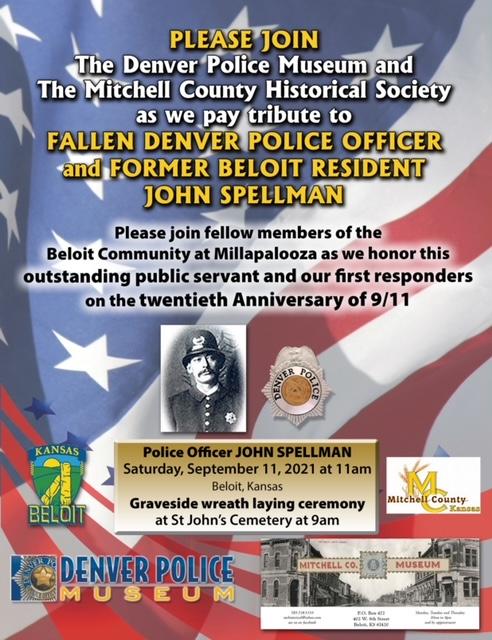

John Spellman

By the time John Spellman came to Denver he was already a seasoned lawman after working as

a deputy sheriff for San Miguel County in the Wild West, gold-crazy town of Telluride, high in the San

Juan Mountains of southwestern Colorado. He began his law enforcement career there after coming out

west from his hometown of Beloit, Kansas, in 1885, when he was only 20 years old. Although the work

was often dangerous, he found he had a natural aptitude for it and soon developed a reputation as an

honest and hard-working officer.

In 1901 he was appointed the master of the guard at the Colorado State Penitentiary in Canon City by

Governor James Bradley Orman, a Democrat. Orman met Spellman and formed a favorable impression

of him in May 1901, when a crisis erupted after 350 miners organized walked away from their jobs at

the Smuggler-Union mine in Telluride. A shooting war was triggered when one of the strikers, believed

to have been unarmed, had been shot through the throat by a deputized mine guard, leading to what

became the greatest crisis during Orman’s administration.

Spellman When Orman was voted out and succeeded by a Republican two years later, Spellman

and many Orman appointees lost their jobs. By this time, Spellman was a family man and decided it was

best to move to the big city where there were better opportunities for him and his family. So, he, his

wife, Mary, and their young son who was also named John but called Raymond, moved to Denver. On

December 8, 1903, he raised his hand and took the oath of office as a patrolman for the Denver Police

Department and pinned on star number 105. For the next three years, for $85 per month, he worked as

a beat cop on the night shift in a part of town most other family men were well advised to avoid after

dark.

It was there on his beat, in front of Vance’s Saloon at 919 19th Street, on a Monday night, June

18, 1906, John Spellman’s life was taken from him by a thug with a gun.

Shortly after 11 p.m. a group of three drunken men, George Turner, Edward Carse and a third

man identified only as West, was creating a disturbance by yelling and cursing in front of the Abbott Hotel, on Curtis Street around the corner from Vance’s Saloon. Spellman walked over and told them to

quieten down. “I don’t want to have arrest you on my beat.” At first, they seemed willing to comply and

started to walk off less raucously towards 19th Street. One of them, Edward Carse, who called himself Kid

Bosco, stopped the other two and told them, “Wait until he gets down near the alley and I will beat his

head off.” They became rowdy again, in an apparent attempt to cause Spellman to take further action

which would give them an opportunity to assault him in the alley. Before that could happen, however,

Spellman caught up to them sooner than they had anticipated on the sidewalk mid-way between the

corner and the alley.

Telling them, “Stop! You are under arrest,” he grabbed Turner by the collar with one hand and

West by the collar with the other and began walking them towards a callbox to summon a police wagon

to take them to jail. Carse remained just out of his reach, standing behind Turner and West. He suddenly

pulled out a revolver and shot Spellman three times in the chest and abdomen. Spellman staggered back

10 feet and collapsed by the saloon doors in the arms of the proprietor, Vance Schneider. The three

suspects ran off in different directions without looking back.

A police ambulance arrived a little later but Patrolman Spellman, 41, was already dead. An

autopsy the next day revealed that the first shot had killed him, piercing his heart. The second shot

entered below his left arm, and the third bruised his chest, then fell into a vest pocket.

Three witnesses gave vivid accounts of the murder.

Leslie Irving, an employee of the Crystal Theater, had just walked out of a chili parlor next door

to the saloon. “I had just come out of the chili parlor when I saw the policeman walk up behind the …

[suspects]. He shouted for them to stop at once. By the time he was close to them and grabbed one with

each hand. No sooner than when he seized the arm of the shorter … [suspect] than the latter turned and

shot twice. Then he backed away and shot again. One of [them] ran down the alley and the other ran

across Champa Street, into the yard of the second house. He fell twice on the way across the street and once inside the yard. I ran into the saloon to get help for the policeman then, but I believe he was dead

by that time.”

Frank Litsey, a Western Union messenger, told detectives: “I was walking toward the policeman

and the two men on the corner were not over 20 feet away when the shooting commenced. The

policeman had each of the men by the arm. The smaller one facing the officer and the taller was looking

toward me. The short … [suspect] called the policeman a name as he turned toward him and then I

heard the shots and saw the policeman fall back against the building. I couldn’t say which one of the

men fired the shots.”

Ross W. Reed, who lived across the street at 918 19th St., saw the shooting also. Spellman and

the three suspects were all clearly visible since the murder happened directly below a bright arc light,

hung above the door to the saloon.

All three suspects were arrested within five hours of the shooting.

West’s role in the murder was discounted early on, and he was released without charges. He

worked as a picker in the beet fields of northeastern Colorado and had become acquainted with Carse

and Turner only a few minutes before the shooting.

When questioned by detectives at the central station both remaining suspects mostly admitted

their role in what detectives theorized had happened; however, Carse said it was Turner who had fired

the shots while Turner swore it was Carse. Turner, 29, had come to Denver a week before from Topeka,

Kansas, where he lived with his wife and small child. He had been acquitted of murder only 18 months

earlier in Kansas City, after claiming self-defense. Carse, 23, was a Denver resident and known to the

police as a “tough” who frequented local saloons and arcades.

The shooter’s identity continued to remain in doubt even after Patrolman Carr found out that an

hour before the shooting Carse, using the name of Moore, had redeemed a $2 loan at a pawnshop a few

blocks away from the shooting scene to buy a revolver. He then sold the gun to Turner for $4, pocketing

a profit of $2. The gun was not immediately found. Fearing that a lynch mob might force their way into the jail at the central station to take Turner

and Carse, on June 21, El Paso County Sheriff Nisbitt took the two prisoners to Colorado Springs. Turner

went to trial in July at the West Side Courthouse and was acquitted after witness testimony and other

evidence strongly pointed to Carse as the gunman. Although Turner was cleared of the murder charge,

Judge Dixon ordered him to be held as the prosecution’s chief witness in Carse’s trial in October. Carse

was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to 10 to 15 years in the state penitentiary. He

was paroled in 1912.

In addition to his wife and son, John Spellman was survived by his parents, five brothers and

three sisters, most of whom lived in or around Beloit, Kansas. One brother, Daniel Henry Spellman, who

was four years older than John, followed his brother into law enforcement and served as city marshal

for the town of Beloit from 1919 until his death from a stroke while on duty in 1934.

Funeral services for John Spellman were held on June 20 th at the Roman Catholic Immaculate

Conception Cathedral at Colfax and Logan, two blocks south of the Spellman family home at 1767 Logan

St. Mary and Raymond Spellman accompanied the coffin on a Union Pacific train to Beloit, where he was

buried in the family plot at St. John Catholic cemetery.

They remained in Beloit and lived for a short time with Spellman’s parents before moving to

Wellington, Utah, in 1910 to live with her parents. Raymond joined the army in 1918 and was honorably

discharged as a corporal a year later. In 1930, Mary was remarried and Raymond was also married. They

all lived in Los Angeles, where Raymond worked as a salesman for a plumbing wholesaler. He and his

wife Frances had a son, Wayne Spellman, born in 1927. Mary died in 1940 and Raymond in 1959.

Wayne died in 1979 and had no children.

Sources

Denver Police Department employment records for John Spellman

Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment Death Certificate 4501, John Spellman

Rocky Mountain News newspaper

The Denver Post newspaper

Beloit Gazette newspaper

Silver Cliff Rustler newspaper

Salt Lake City Herald newspaper

Los Angeles Herald newspaper

Las Vegas Daily Optic newspaper

United States Census records for 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930 and 1940

Keith Dameron, historian, Colorado Law Enforcement Memorial