These Black women changed how the Denver Police Department hires new officers

By

Rosie

/ February 28, 2022

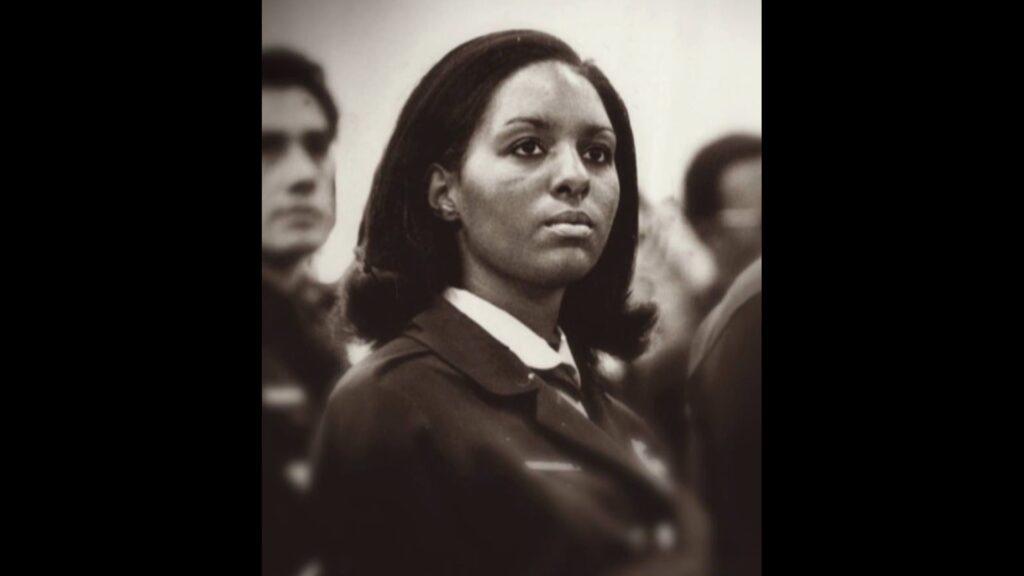

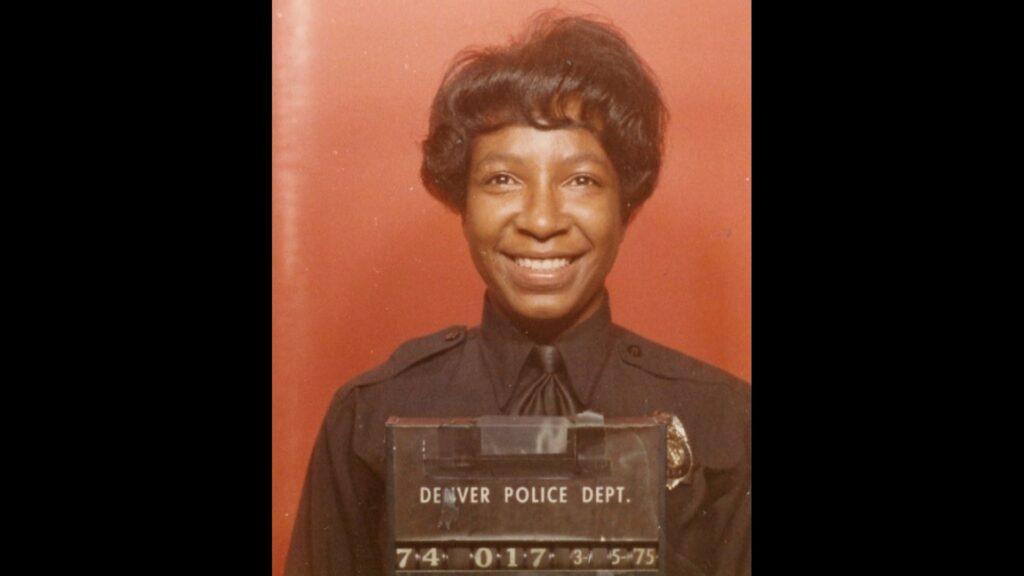

Rae Beth Hunn, Laura Tinnin-Whitney and Carol Hogue sued when DPD first rejected their applications to become officers in the '70s. It changed history.

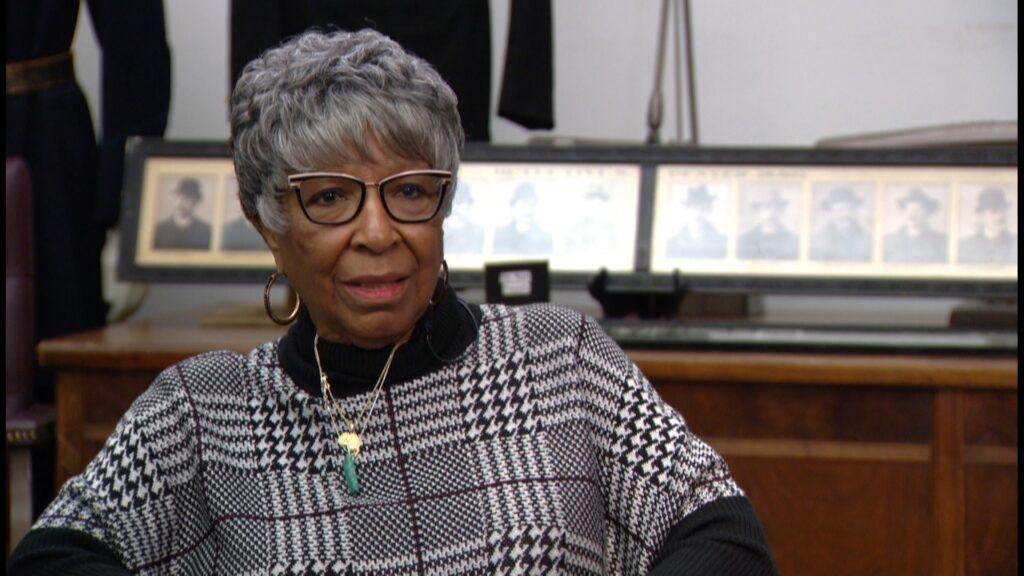

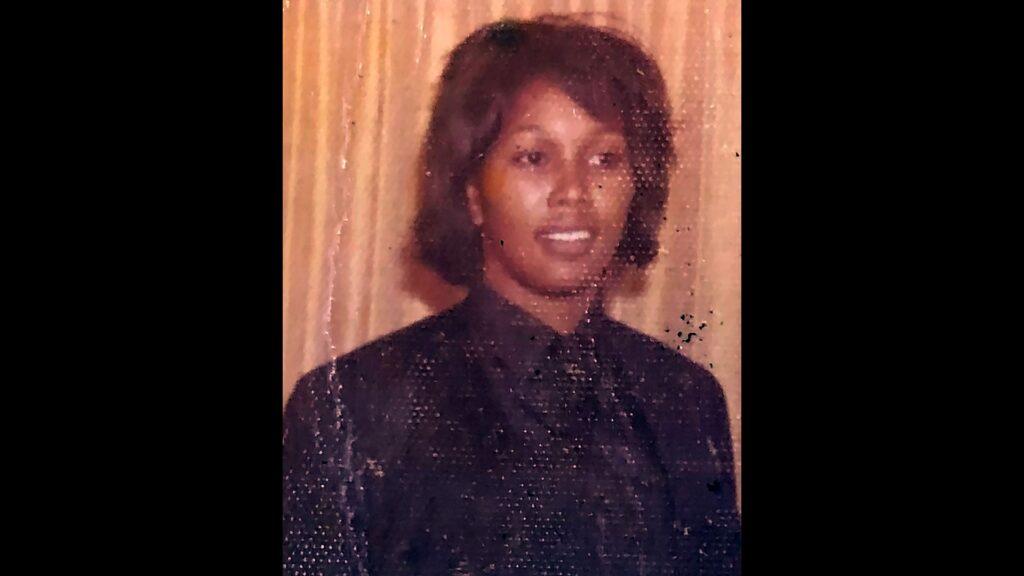

Laura Tinnin-Whitney

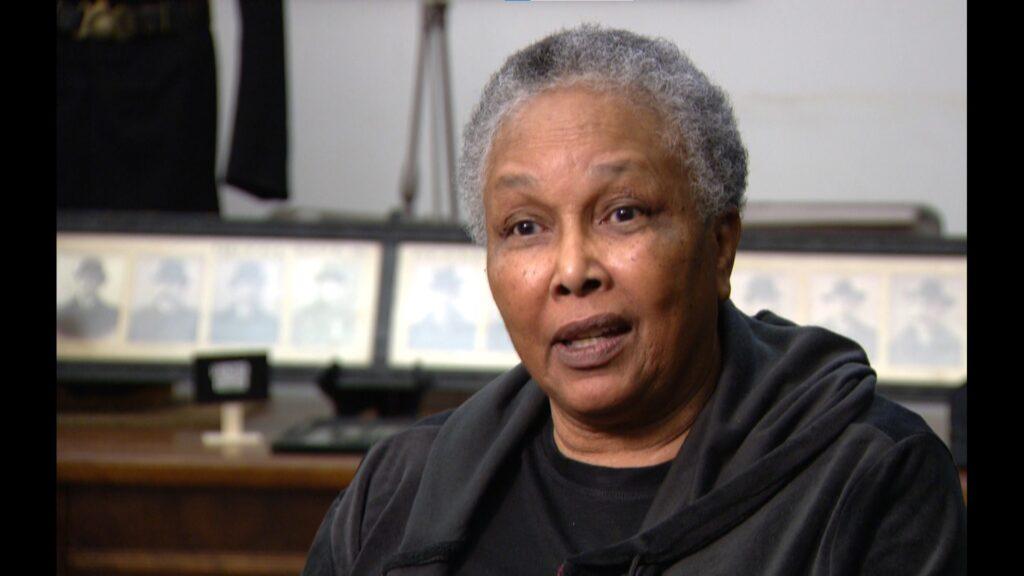

Rae Beth Hunn

(9News) DENVER — The Denver Police Museum recently honored Rae Beth Hunn, Carol Hogue and Laura Tinnin-Whitney for Black History Month. The three women fought racism and discrimination in the early 1970s so that other women of color could have the opportunity to serve as law enforcement officers for the Denver Police Department (DPD). “It was rough,” said Hunn. “I felt it more in the department because of the isolation.”

The Denver Police Department had Black male police officers serving since the 1870s. In the late 1960s, women across the nation were joining the ranks of patrol officers across the country but the recruitment and hiring of minority officers in Denver lagged behind the national average.

“I wanted to fight for what was right,” said Tinnin-Whitney. “I knew it would be rough, but it made me a better person and I’m glad I did it.”

In 1972, Hunn, Carol Hogue and Tinnin-Whitney applied with the department but all three were rejected.

They ended up suing the City and County of Denver, Denver Civil Service Commission and Denver Police Department for discriminatory hiring practices. Their claims were that women and minorities were not represented fairly in the department. The city eventually settled the lawsuit and agreed to implement changes. That settlement is still known today as the Hogue Decree.

“I really observed and saw this had to change, and we did make a change,” Tinnin-Whitney said. “We said, ‘Something’s not right here. There are no Black women on the job. We need to do something about it.’”

The first three Black female officers hired were Carole C. Hogue on June 6, 1972; Rae Beth McCall on July 2, 1973; and Laura M. Tinnin on February 1, 1974. Hunn and Tinnin-Whitney were partners their first years on the force working in the traffic division. It was a job they say they said that came with problems.

“The discrimination was great and to come on as a Black woman as a result of a lawsuit — it was rough,” Hunn said.

“She had my back and I had hers,” added Tinnin-Whitney. “We would ask for cover, sometimes they would show up, sometimes they wouldn’t, but we had each other’s backs.”

Hunn went on to become the department’s first Black female detective and worked in the department until 1979. Tinnin-Wheatley retired from DPD after a 30-year career. Hogue now lives in Florida.

These three pioneering Black women were involved in the city of Denver’s 1988 agreement to include 45 percent Black officers in the first academy class of 1989 and to make a good faith effort in recruiting academy classes to reflect the demographics of the city. “When I heard that story, I was not only grateful, but I was inspired,” said Sgt. Carla Havard. “I felt as if they passed along a baton to continue what they have started and that is making sure that Black women are valued and that we’re part of this institution of policing.”

Havard is a 24-year veteran of DPD and serves as the president of the Denver Black Officer’s Organization. She said she’s inspired by the strength and courage of these three women.

“They were courageous enough to sue this entity of the Denver Police Department saying, ‘Yes, I am valuable, and I can do this job as well,’” she said. “You talk about courage and to see them today is a testament to the resiliency of people who are on the right side.” “There were times when I thought about quitting,” added Hunn. “But I said, ‘I can’t do that because there’s a young Black girl behind me that will want this job.’”

The Hogue Decree is still in effect today. Female officers are 14.5 percent of the Denver Police Department and the department continues to focus on encouraging women in leadership roles.